<voltar>

<voltar>

Cultist Simulator is a game about experimentation.

You begin by staring at a big empty board, which contains just two elements: a card called “Menial Employment” and a slot called “Work”. Not knowing what to do, you inevitably slide the card into the slot, and ding: a timer appears. After waiting for circa 10 seconds, the slot spits your card back along with two rewards: a golden coin card (your payment) and a “Health” card (meaning that your job makes you feel rested).

And in just these few moments, you’ve learned the two core mechanics of Cultist Simulator: sliding cards into slots and waiting for things to happen.

Although these actions may sound simple, they are only the interface of a very complicated machinery. There are multiple slots other than "Work" - not to mention hundreds of cards -, and since the same slot can produce wildly different results depending on the card you provide, there is an explosive number of combinations. Of course, not all combinations are viable or useful, but since the game offers no tutorial or hints of any kind, the only way to navigate the possibility space is through trial-and-error. If sliding cards into slots is the game’s main action, then experimentation is the game’s true essence.

At first glance, this mandatory experimentation might seem challenging enough, but I guarantee you that it is even worse than it sounds: it’s not only about not knowing how to do stuff - you don’t even know what you’re trying to do. The game is called Cultist Simulator so it stands to reason that your goal is to join (or start) a cult, but how exactly, and then what? You truly feel totally lost. It is not like the game is a sandbox either: there are definitely ways to complete a playthrough, it’s just that you just don’t know what they are or even what they look like.

Amidst this severe lack of information, it is not at all surprising that many people found the game to be frustrating. The Steam reviews for the game are overall positive, but it is not hard to find comments along the lines of “Avoiding hand-holding is fine, but you devs have taken it too far this time!”.

https://commento.vgarcia.xyz/

https://commento.vgarcia.xyz/

And I understand the feeling, but I must confess that it didn't bother me in the slightest; on the contrary, it felt great! It created a deep bond between myself and my player character: the process of understanding the game’s mechanics perfectly mirrored the process of my character gradually understanding the rules of the occult, and as my character progressed within the cult, I started to grasp the game’s lore. The entire experience was exhilarating – I loved not knowing what to expect, and the constant surprises that this brought me. I often felt lost, yes, but the time spent improductively bumbling about was more than compensated by those few moments of clarity, where things suddenly clicked and the floodgates of progress opened once again. I had to resort to Google once or twice, but this is also a price I agree to pay; after all, aren’t all great puzzle games like that?

Of course, none of this would have been possible if the game had a tutorial. That would’ve missed the point, because the fun of Cultist Simulator is finding out what is Cultist Simulator. And as soon as you do it, the game changes. Because, at its core...

Cultist Simulator is a clicker game.

At some point in your Cultist Simulator experience, you will realize that game progression requires something called “Lore” cards. “Lore” are basically Pokémon types: there are 9 of them, and they all have weaknesses/strengths against each other (Lantern beats Moth, Moth beats Grail, Grail beats Heart, etc). Each of these “Lore” cards has a type and a level (e.g. “Heart lvl 4”, “Winter lvl 10”), and game progression requires specific “Lore” cards: for instance, you may reach a point in the game where you need either a Knock, Lantern or a Winter card with level 4 or higher. At first this might sound harmless, but let me tell you the consequences of such a requirement.

The way to obtain these “Lore” cards is by sliding book cards into the “Study” slot, which is simple enough. The problem is: how to obtain the book cards? Well, in the early game you can simply buy them from shops, but since the books you require become increasingly rarer, in the middle- and late-game you need to find books by sending expeditions to cursed locations. The “expeditions” mechanic works like this: you select which cultists you want to send on an expedition, and then you wait for a few real-life minutes for the expedition timer to conclude. After that, your minions either die, or return with your much desired book(s).

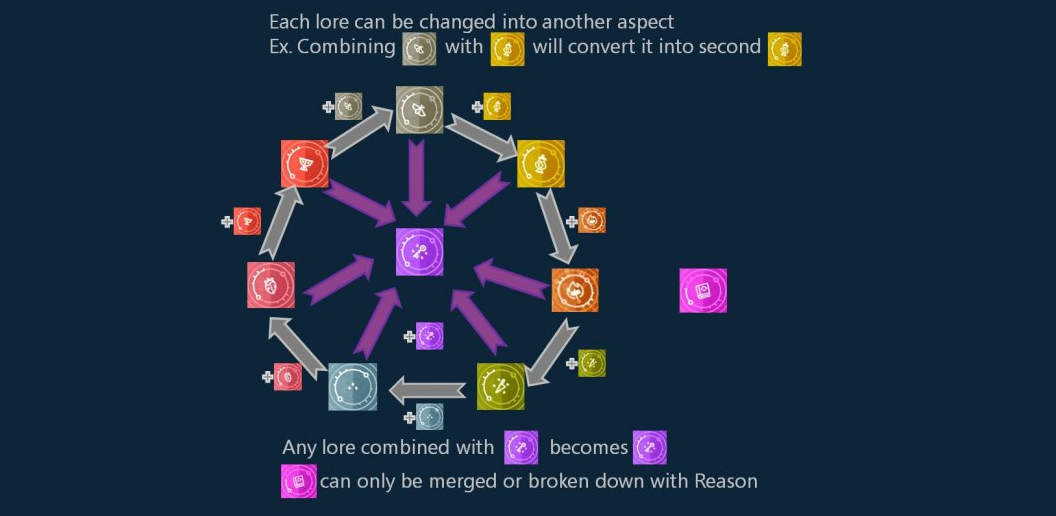

Of course, the book you get is just a book, and it might not be the book you need... That is why you have to use the Lore conversion mechanic! (This is where I subtly pull out my conspiracy corkboard). Lore conversion works like this: if you slide two “Lantern lvl 2” cards into the “Study” slot you will get a “Lantern lvl 4”, because 2 + 2 = 4. Simple, right? But if you slide a “Lantern lvl 2” and a “Moth lvl 2” you will also get a “Lantern lvl 4”, because Lantern beats Moth, so it converts the Moth into a Lantern, see? Oh, but what if I only have a “Moth lvl 1”, I can hear you ask... Well then, since Moth beats Grail, you can use a “Grail lvl 1” alongside your “Moth lvl 1” to obtain a “Moth lvl 2”, and then use that “Moth lvl 2” with the “Lantern lvl 2”, and then…

And then you’re drawing shit like this:

If this sounds nothing like the experimentation that I described before, good! That’s exactly the point. After you grasp the mechanics of Cultist Simulator, the only challenge left is to mind-numbingly repeat the same actions over and over again for hours on end, hoping to drop the book you need. Game designers have proposed a thousand definitions for “fun”, but this falls under none of those.

There are two games within Cultist Simulator.

Game number one covers the first 5 or 6 hours of gameplay, and it is about experimentation: you have no clue of what’s going on and it’s wonderful. It is a game that makes you ponder over every item description, because maybe this information will help you to solve puzzles like “What’s behind the Peacock Door?” or “What can I do in the dream world?”. It is quite an experience, and I would strongly recommend the game based on those first few hours alone.

Sadly, there’s game number two. This second game is about repetition: you know exactly what to do and how, and the challenge becomes turning off your brain and doing it. It is a boring and grindy game, and I would not recommend it to anyone.

Or maybe it would be more accurate to say that the game doesn't change - it's the player who does. As you transition from “I don’t know what to do!” to “I more or less know how this game works”, the experimentation becomes less and less necessary, which in a risky roguelite-y game like Cultist Simulator means that it simply disappears. The initial vast sea of possibilities gives way to a definite, encyclopedic knowledge of the game’s inner workings, and then you realize that you're not having fun anymore.

Now, I want to clarify: not everyone likes figuring things out. There are some players (like me) who derive pleasure from mystery and experimentation, and there are others (like the reviewer I mentioned earlier) who aren’t that comfortable with being confused. And that’s okay, there’s enough space for both of us here. However, I will argue from the point of view of the first group, and in particular the point of view of someone who was enlightened by merely realizing that there are two groups.

Because once I realized that most games have two phases - “figuring stuff out” and “doing stuff” -, and that I mostly preferred the first one, a huge part of my relationship with videogames started making sense.

I have always found long games to be kind of a chore, but I never understood why; by employing this framework of “figuring out” vs. “doing”, it became clear. The first few hours of every game are the most full of surprises, as you struggle to understand what are the rules, what the game expects of you, what’s the rhythm of gameplay, what’s possible, etc. However, once you grasp those concepts, the rest of the game is usually just more of the same, and the challenges become skill-based rather than intellectual. The 17th level of Super Mario might introduce a new mechanic, sure, but it’s still about moving right and avoiding enemies. The superficial may change but the core stays the same, and as long as the core stays the same, the game remains unsurprising.

Breath of the Wild is a good example. At first, I was truly enchanted with the game: it gave me an unparalleled sense of freedom, as I walked over Hyrule climbing every mountain. But 10 hours in, I had already figured out all the possible things that could be on top of a mountain: a shrine, an enemy, a Korok Seed, or one of those skull-shaped goblin houses. Once I realized that, climbing mountains became much less interesting. The same process extended to the rest of the game: I knew what I could find inside a shrine, what the dungeons were like, what was the purpose of most of the game’s items... The realization that the game held no other major surprises in store, in addition to the realization that I wasn’t even halfway through the game, led me to wistfully drop the game then and there, because I wasn't interested in repeating the same actions for 40 more hours. This has been my experience with most long-ass games.

I love Outer Wilds because it cleverly avoids this trap of “being too long”: once you figure out how the world of Outer Wilds works, the game simply ends. And this is no exaggeration: you can actually complete the game in less than 10 minutes if you know exactly what to do and where to go! The problem is, of course, that you don’t know these things at first, and it takes the whole game to figure them out.

This is by design: player progression in Outer Wilds is measured not by levels, or inventory, or even by hidden game states (e.g. which chapter you are in the narrative), but only by the information accumulated by the player. Therefore, once you know how the game works, you’re already at the end of it – even if you start a new file. In this sense, the entire game is like a puzzle, which can't be "figured out again" once the solution is known. This is in stark contrast with basically any other game: you can play Cultist Simulator over and over again even if you’ve already understood the mechanics, because there are other challenges, repetitive as they may be; Outer Wilds, on the other hand, has no other challenge.

By putting the challenge of “figuring stuff out” at the forefront of its game design, Outer Wilds became one of my favorite games.

And if Outer Wilds is about “figuring stuff out”, then Dark Souls is about “trying to figure stuff out and failing miserably”.

When people say that Dark Souls is hard, they usually talk about the skill stuff: the enemies deal way too much damage, you drop your souls when you die, you have to walk all the way to the boss every time, etc. However, these are only the more skill challenge-y aspects – what about the experimentation stuff? What about not knowing that you should upgrade your weapon, or not knowing which skills to put points into, or not even knowing if you’re going in the right direction? There is a dense atmosphere of confusion inherent to the Dark Souls experience, which Brendan Caldwell summarized best:

“At no point during my first run of Dark Souls did I have any idea what I was doing. Not only in terms of the story, if it can be called a story, but also in my actions. A strange man would ask me a question and I would answer in the affirmative, not understanding why. I would equip a new weapon and wonder why I was suddenly rolling more slowly. A frog would burp on me and I’d panic that half of my health bar was now missing”.

Dark Souls is filled to the brim with this pattern of “I have to make a decision but I do not know what the fuck is going on”. A few months ago I was watching my girlfriend play the game for the first time, and I realized that this happens literally in the goddamn character creation screen, when you have to choose a starting item without any context of which is in your best interest. Only cryptic descriptions guide you: “A trinket”, “Ancient ring with no obvious effect”, “Tiny sprite called humanity”. Brother… I don’t even know what a humanity is, let alone if I should want it!

This is the hardest aspect of Dark Souls, I’d argue: not the fidgety combat stuff, but how it defies understanding. And this is also in stark contrast to most other games: while the point of “figuring it out” happens halfway through Cultist Simulator, and right at the end of Outer Wilds, in Dark Souls it never fully happens. Sure, you understand more of it at the end, but it certainly doesn’t feel like much. When I finished Dark Souls for the first time, I actually had no clue of what I’d done storywise, and many of its mechanics still eluded me: I didn't know that I could kindle bonfires, or what humanities were for, or why sometimes I just regained an Estus Flasks out of thin air (still don’t know that one!).

Sure, it’s great to beat a boss that’s been giving you a hard time. But I’d wager it’s even better when an item description leads you closer to understanding the game’s story, or when you find a shortcut and the whole world clicks into place. Dark Souls only became a household name because of the veil of mystery that looms over it, not in spite of it. If Dark Souls weren’t so refreshingly mysterious, it would be just another mediocre action game that’d be forgotten in less than a year...

But if you want to analyze what Dark Souls would be like without its mystery, you don’t have to resort to such thought experiments: you can just play the other games in the series!

Indeed, Dark Souls 2 and 3 are so similar to Dark Souls 1 that once you figure out the first one, you figure out the other ones as well. The levels and enemies differ between games, sure, but those are only superficial changes – the core stays the same. Dark Souls teaches you to avoid ambushes by paying attention to its environment; once you know how to do that, you can apply the exact same lesson to Dark Souls 2 and 3. Leveling up is a confusing part of Dark Souls (where do I do it? do I have to do it? which attributes should I emphasize?), but once you know that, it’s pretty much the same in the other two games. Apply enough generalizations of this kind, and the inevitable consequence is that for a veteran of Dark Souls, the other games in the series present little mystery, other than the particular instances of their respective worlds. As Tevis Thompson pointed out:

"Mystery cannot abide formula. Over time, the iterative nature of most games kills mystery. It’s not just the story questions answered in a sequel. It’s the world and mechanics that are already known, given, expected even. A videogame sequel begins with most vital questions already answered. Who am I? Where can I go? What can I do? How does the world work? What are the limits? Instead, I only ask: What’s different this time? Is it better than the last one? Can I dual-wield?"

Heck, such generalizations apply even to Sekiro! In 2019, an youtuber called Iron Pineapple got flown to NYC to play a preview copy of Sekiro. In the first 20 seconds of gameplay, he arrives at a starting area where a blue fire burns in the middle. He then says: “Hmm. This seems like the new Firelink. Is this like a bonfire?”. And boom: in less than a minute, he has already figured out that there is a central area important to the plot where he’ll frequently return and where NPCs may gather ("the new Firelink Shrine"), and he now knows that the blue fires are places where you can level up and maybe teleport ("the new bonfires"). Sure, he doesn’t actually have confirmation of this knowledge, but it still changes now he sees the game - now he has a point of reference which will serve to ground his experience. The question that then emerges is: if he hadn’t played Dark Souls, would he enjoy Sekiro more? Of course there’s no way of knowing, but I think we all can agree that at least he’d find the game more mysterious. And in my book, mystery is good.

This is why other soulslikes just don’t cut it for me: if you want to present an experience similar to Dark Souls, you have to defy understanding as well; but you cannot defy understanding by copying the structure of a game that’s already well-understood! In that sense, if you want to have an experience similar to playing Dark Souls for the first time, it's more beneficial to play Outer Wilds than to player Dark Souls 2 or 3 or Nioh or Lords of the Fallen!

Which is why…

If you like Super Mario, you probably like it for the platforming and the skill challenges involved. In that case, searching for other games you might like is easy: you just google “games like Super Mario” or “good platformers” and you’re set! Maybe you won’t like all of them, but it’s a good place to start.

However, let’s say you felt exhilarated with the mystery of Dark Souls, and want a hit of something similar. If you google “games like Dark Souls” or “good soulslikes”, you will find a barrage of games that are mechanically similar to Dark Souls – but as we’ve established, this is exactly the type of game that won’t give you a similar experience, since you already understand most of their mechanics!

Because of this unfortunate state of affairs, it is very hard to find games with mystery vibes similar to the ones that you already like. The concept of genre would be useful here, however there is not a single genre that would encompass the type of experience of which I am talking about – games which involve you “figuring stuff out” (and admittedly, even my definition is somewhat vague). The “mystery game” tag has some potential, but it is currently synonymous with “murder mystery” and “detective games”, which doesn’t seem to be changing anytime soon (even though the Outer Wilds’ Steam description calls it an “open-world mystery game”). “Exploration game” is also an interesting label but most people use it as synonymous with “open-world”, so it also doesn't work. Finally, no one uses “experimentation game”.

Therefore, there is not a good reliable way for finding games of this kind. Here is a list of games that I feel “scratch that itch”, and as you’ll see, there isn’t any genre that’s common to all (or even most) of them:

When people asked me what my favorite games were, I’d usually say something in the lines of: “oh you know, exploration games like dark souls, fez, minecraft etc”. However, over time I gradually realized that this was not a thing – nobody understood what I meant by “exploration games”, and to make matters worse, I could not define it either.

I still can’t define it, but through this essay I attempted to convey the spirit of mystery and exploration – the feeling of “figuring things out” that made me fall in love with videogames. I hope I could make myself understood. If you are interested on the subject, here are some other links that explore similar ideas: